Crowdsourcing the Asylum

What happens when you care what people think?

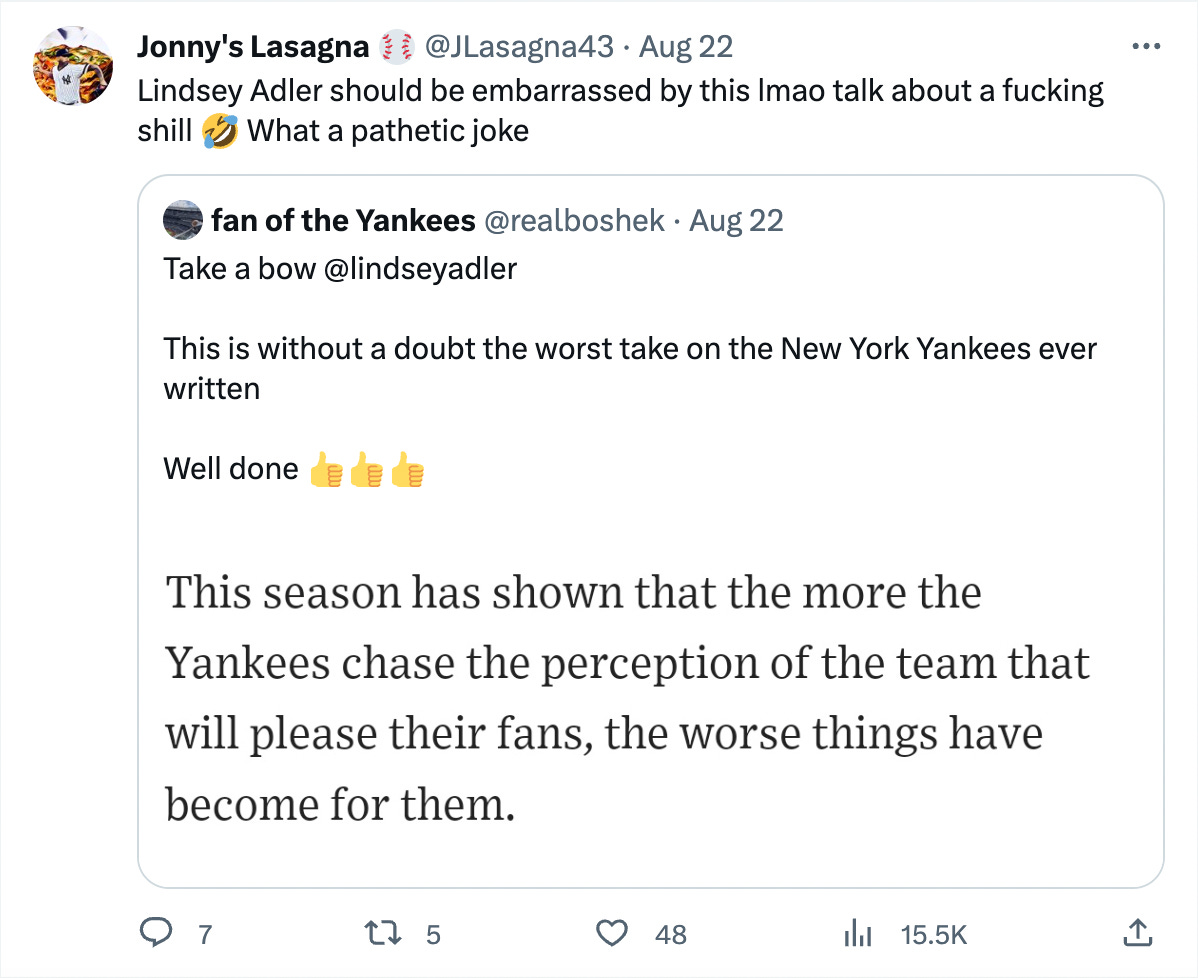

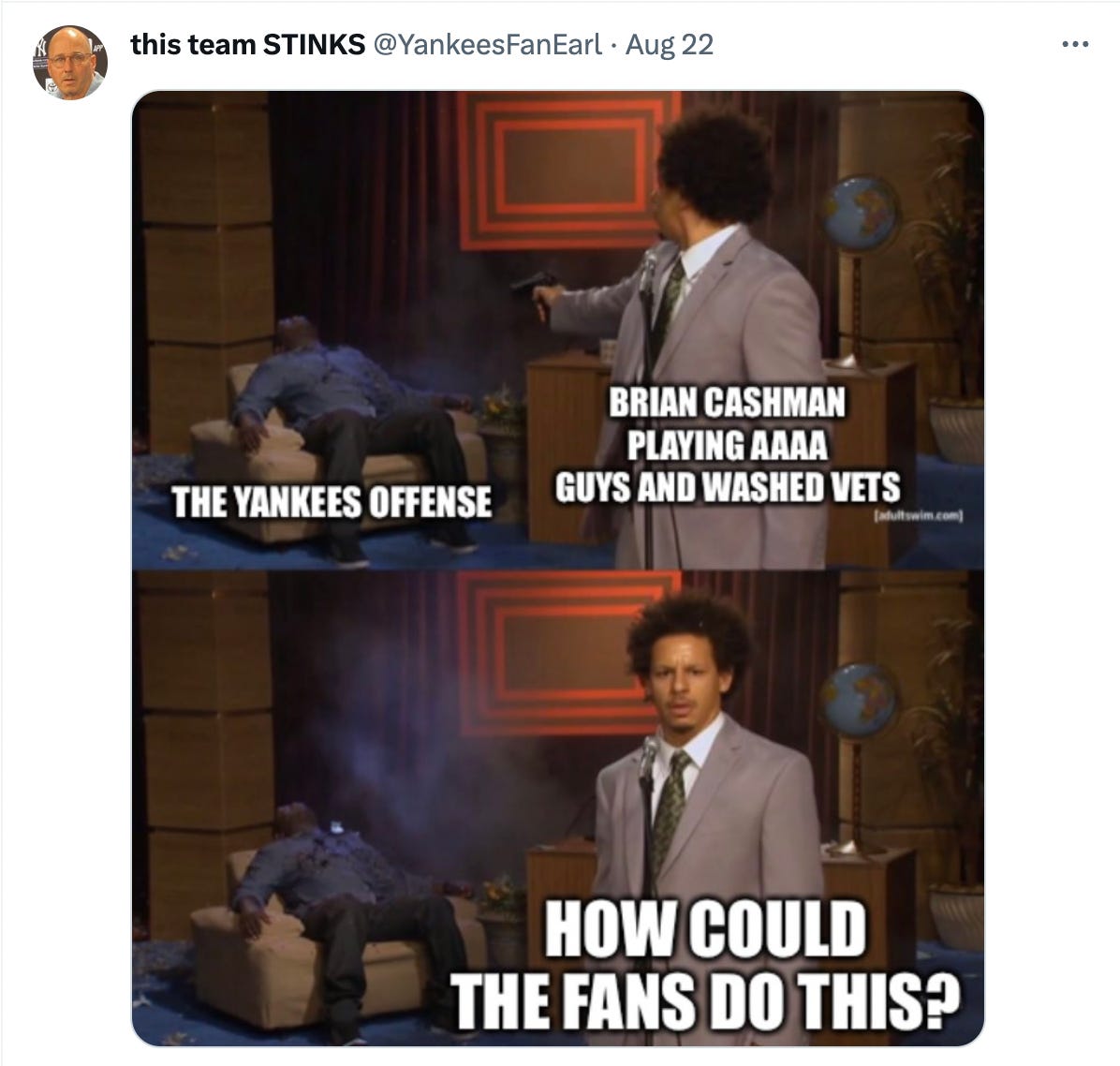

Last month, Lindsey Adler wrote an article for The Wall Street Journal that sent Yankeeland into a tizzy, ostensibly arguing that the Yankees’ recent failures are the result of the front office kowtowing to the fanbase’s whims. I say ostensibly because I’m not a WSJ subscriber and didn’t read it. But let’s be real— having strong reactions to articles you didn’t actually read is the bedrock of social media discourse. And it’s not like any of these dudes read the article, so I’m just playing down to the competition here.

Other fans agreed with Adler, and it got me thinking— how many actual examples are there of the Yankees trying to appease their fans? What’s the success rate there? How about times they made unpopular decisions? Do those tend to work out better? As apparently Buddy Ryan once said, “if you listen to the fans, you’ll be sitting up there with them.” That definitely sounds right, but if the Yankees don’t think that way, would it really make Yankee fans any happier if they did?

To me, the classic examples of a team making baseball decisions to placate its fanbase are ironically both from the Wilpon-era Mets. One of the most oft-cited pieces of Mike and the Mad Dog lore is the time they helped orchestrate bringing Mike Piazza to Flushing. To hear da Sports Pope himself tell it:

The other is when they re-signed Yoenis Céspedes the second time. Before 2022-23 Aaron Judge, 2015 Céspedes was arguably the best recent example of a single player having a profound impact on his team’s success in baseball. Without him, the Mets were three games over .500, batting guys like Eric Campbell cleanup and posting a sub-.700 OPS as a team. With Céspedes, they posted a team OPS of nearly .800, en route to winning the 2015 National League pennant. After the 2016 season, Céspedes opted out of his contract, and fans clamored for the notoriously stingy Wilpons to give him a new one. Some argued that the Mets owed it to their fans to bring him back. The Mets acquiesced, signing Céspedes to a four-year, $110 million deal.

Thanks to a series of hamstring injuries in 2017, season-ending heel surgery in 2018, an alleged wild boar attack in 2019, and Céspedes’ bizarre decision to abandon the team and use his COVID opt-out in 2020 because he “wasn’t having fun,” he’d never play another full season with the Mets. Hey, one outta two ain’t bad.

But these are the LOLMets we’re talking about. Do the Yankees resort to PR panic moves like these? The first thing that comes to mind is Alex Rodriguez’s second contract. After a monster 2007 season, A-Rod famously announced he was opting out of the final three years of his 10-year contract during Game 4 of the World Series. The Post wrote that the move would “almost certainly” end A-Rod’s tenure in the Bronx, as the Yankees were reportedly not willing to negotiate with him due to the opt out costing the club $21.3 million in future subsidies from the Rangers. But less than two months later, the Yankees caved, and gave him a brand new 10-year deal worth even more than the last one. No other team in baseball was sniffing 10 years, $275M for A-Rod. Ultimately, the fear of losing their best player, and one of the marquee names in sports, pushed the Yankees to bid against themselves.

A similar thing happened with CC Sabathia, who didn’t exercise his opt out after the 2011 season, but did manage to negotiate a contract extension to keep himself in pinstripes through 2017. Essentially, the Yankees agreed to rip up the biggest free agent contract for a pitcher in baseball history, and replace it with the biggest one by annual average value. I remember Sabathia’s preference for the west coast and the National League in the lead up to his first deal with the Yanks, but I don’t recall many rumors of other teams swooping in and prying him away when the opt out loomed. This was during the Dodgers bankruptcy saga, and other than maybe the Red Sox or Angels, I can’t think of any other teams that would’ve paid Sabathia more than what he was already getting. But the extension happened the same offseason that Cliff Lee spurned the Yankees, and like Rodriguez, Sabathia capitalized on the front office’s desperation.

I’d say that Yankeeland remembers more good than bad from Sabathia’s second contract, and more bad than good from A-Rod’s. Certainly, A-Rod’s lows were louder, and he was just never popular with fans or media, but I’d argue that Sabathia’s second deal was worse. From 2013-2015, he posted a 4.81 ERA, and like Rodriguez, he had off the field issues. It didn’t really matter thanks to Dallas Keuchel, but Sabathia had to leave the Yankees the day before the playoffs started to check himself into an alcohol rehabilitation center in 2015.

He’d reemerge in 2016-17 as a serviceable finesse pitcher, inducing soft contact via his newfound cutter, and even managed to earn additional one-year deals in 2018 and 2019. I think it’s weirdly this post-prime phase of his career that most ingratiated him with Yankee fans. But it always seemed like the team put too much faith in him, letting him lose consecutive postseason elimination games. The gritty image of him adjusting his knee brace between pitches endures, but I think back to how it was just accepted that Sabathia couldn’t cover first base. In an age where fans and media began to reassess baseball’s Unwritten Rules with a critical eye, Sabathia was calling the Red Sox “weak” for bunting against him, because it’s bush to make a fat guy run:

No matter what you think of A-Rod, the Yankees owe their last World Series title to him more than any other single player. Still, by the mid 2010s, both contracts cast a pall over roster construction, at one point pushing the Yankees to be the only team in baseball not to sign an offseason free agent to a major league contract.

Along with Mark Teixeira, A-Rod and Sabathia were the main reasons for the Yankees’ general lack of spending from 2013 to 2016. While the team’s payrolls were still very high as a result of the players who were already on the books, the typical Yankee offseason back then was marked by moves like passing on the Max Scherzers of the world, and seeing what the Kevin Youkilises had left in the tank.

There was one notable exception. The Yankees went on a spending spree during the 2013-14 offseason, dropping a combined $438 million on free agents Brian McCann, Jacoby Ellsbury, Carlos Beltrán and Masahiro Tanaka. I remember seeing some later interview with Hal Steinbrenner where he said he splurged because he felt he owed the fans a championship contender, but in reality it was a mea culpa for letting Robinson Canó leave in free agency, a two-part act which in itself was some serious fan appeasement calculus. Canó was a homegrown star on a Hall of Fame trajectory — this, of course, before some stuff happened — but he never captured the hearts of the fans the way the Core Four did. Yankee brass knew they could withstand losing him, and that spending on an assortment of other biggish names would gloss over any hard feelings.

But it wasn’t money well spent. Tanaka’s seven-year deal ultimately has to be viewed as a success, and he’s still beloved by fans and remembered as a big game pitcher. But after posting a 2.77 ERA in 2014, it’s hard not to think what could’ve been had he not suffered a partial UCL tear. Following Adam Wainwright’s lead, he opted to rehab the injury instead of getting Tommy John surgery, and for the remainder of his Yankee career sported diminished velocity and a fastball that frankly "stunk." McCann had a .731 OPS in pinstripes, and Ellsbury’s contract was such a disaster that the team tried to weasel out of paying it. The Beltrán deal actually went about as well as a contract covering a player’s age 37-39 seasons could go, but that they dealt him at the trading deadline two seasons later indicates how poorly these signings worked out. It’s easy to imagine a less scrutinized team in a smaller market simply bidding farewell to Canó and calling it a day, maybe even being so bold as to market their financial prudence instead of shiny new free agents.

Fast forwarding back to the present, DJ LeMahieu appears to have caught second wind since this year’s All-Star break, but the six-year deal the Yankees gave him after the 2020 season has largely looked like a mistake. It’s easy to forget, but in the not so distant past, it was LeMahieu, not Judge, who fans and media considered the heart of the Yankees’ then-prolific offense. In fact, the initially unpopular decision to sign LeMahieu over Manny Machado or Bryce Harper was hailed as a shrewd move just months into the 2019 season. But would say, the Dodgers have felt so compelled to re-sign a 32-year-old middle infielder? They let star MIFs Corey Seager and Trea Turner walk in the middle of their primes. The Astros didn’t bend over backwards to keep George Springer or Carlos Correa. The Yankees seem to be alone in their self-imposed duty to retain all of their fan favorites.

All these moves have yielded mixed to poor results, but what about ones that worked out well? To me, it then becomes sort of a semantic argument. I immediately thought of Bernie Williams, who in the winter of ‘98 nearly signed with the Red Sox before George Steinbrenner bowed to his demands on Thanksgiving eve. The threat of losing arguably their best player to their most hated rival was enough to push the Yankees’ offer up by more than $50 million, but Williams would go on to be the club’s best hitter from 1999-2002, so does anyone care about the how or why of that contract?

Using the biggest recent example, there was no possible way the Yankees could’ve weathered the PR fallout of Judge signing with the Giants. But if the next eight years are chock full of Judgian blasts and, ideally, the raising of championship flag(s) plural, will that deal be remembered as the one Hal frantically paused his Italian vacation to close under threat of media blitz, or just a simple no-brainer?

Fair or not, a contract probably has to age poorly to be remembered as principally fan driven. But if you ask me, the Yankees’ most craven acts of fan service were the sanctimonious farewells for Mariano Rivera and Derek Jeter in 2013 and 2014. Jeter and Andy Pettitte walking out to the mound to take Rivera out of his final appearance has to be the lamest thing I have witnessed as a Yankee fan. Where “RAWJA CLEMINS IS IN GOAWGE’S BOX” was campy and fun WWE-style theater, papering over a meaningless September game by having Jeets and Pettitte take the ball from a sobbing Mo was Hallmark schmaltz. Getting Metallica to play “Enter Sandman” live in center field was pretty sick though.

These were stunts Hal & Co. realized they could pull in lieu of putting a winning product on the field. As I write this, the Yankees just wrapped up a bizarre Old-Timers’ Day where an awkward on-field Q&A replaced the traditional game. Commemorating the 25th anniversary of the ‘98 team makes perfect sense, but milking nostalgia (“Glory Days” by Bruce Springsteen played at the end) as the Yanks sit eight games out of a playoff spot in September is low-hanging fruit. No franchise in sports has the Yankees’ history to draw upon, and the team conveniently goes back to the well whenever the present gets stale.

There are stunts the Yankees can’t pull though. Where the Astros or Orioles can tank for several years, accruing a wealth of prospects while racking up 110-loss seasons, Hal has said that tanking isn’t in his DNA. Translation: he knows that the shitstorm it would cause if the mighty Yankees were intentionally bad for half a decade just wouldn’t be worth the eventual payoff. As is, being Pretty Good every year has pushed the franchise’s value north of seven billion dollars. Why mess with that?

There are also strategic moves the Yankees can’t make, right away at least. Where the Rays can test out unorthodox shifts and bullpen usage in anonymity, the Yankees are The Yankees, and as we saw after the infamous decision to use Deivi García as an opener in Game 2 of the 2020 ALDS, if the Bombers go outside the box and fail, there’ll be hell to pay. I remember an MLB Network segment in 2017 where Brian Kenny suggested the Yankees try “bullpenning” the American League Wild Card Game, and as anyone who watched that game knows, they basically did have to do so on the fly. With the deepest bullpen in baseball at the time, the Yankees were uniquely equipped to eschew a traditional starter in favor of a parade of relievers, but they couldn’t risk their brand by being the first to break with convention. Bullpenning and openers took the league by storm in 2018, and in 2019, the Yanks finally started utilizing Chad Green the way Kenny had suggested two seasons earlier.

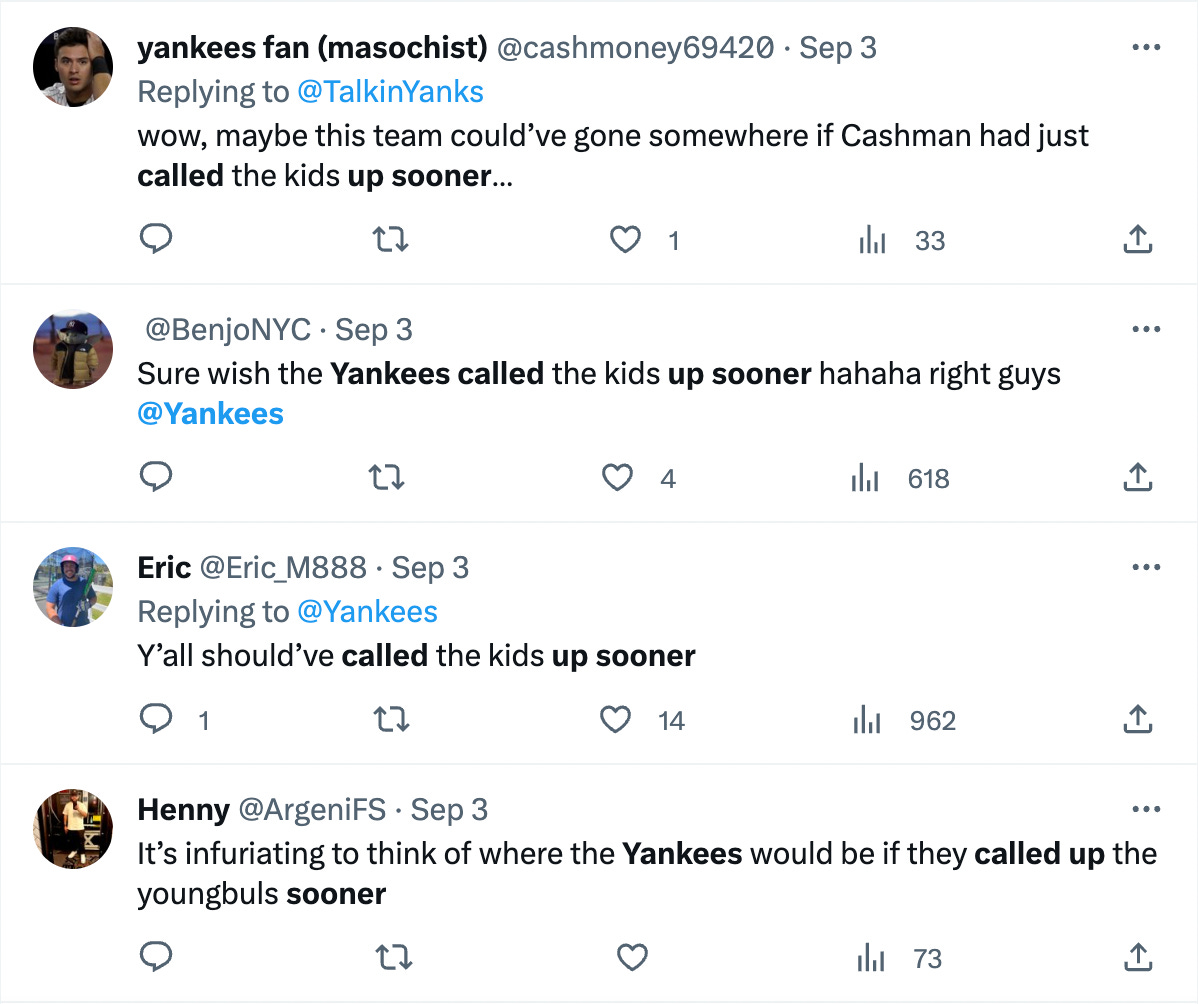

While the Yankees aren’t likely to spearhead any league trends, they have recently broken one of their own. Starting with the decision to name Anthony Volpe the Opening Day starting shortstop, the team has gotten more aggressive with promoting their young prospects, culminating with the September 1st promotion of top prospect Jasson Domínguez— six months before his 21st birthday, with all of nine AAA games under his belt. Along with recent call ups Oswald Peraza, Everson Pereira, and Austin Wells, it signaled a changing of the guard for what has long been a veteran laden roster. So why the sudden change of heart?

The common thread is Yankee Global Enterprises, LLC’s bottom line. Hyping Volpe up as the shortstop heir apparent dates back to 2021, and has given Hal license to pass on a bevy of big name free agents, from Seager and Correa, to Turner and Xander Bogaerts. Naming Volpe the major league SS not only gave fans what they’d lobbied for all spring long, it formally kickstarted the Favorite Son marketing campaign. Volpe not only grew up a Yankee fan in New Jersey, his parents are Yankee obsessives whose first dates were in the Yankee Stadium bleachers. He didn’t just idolize Jeter, there’s a picture of him meeting da captain as a kid. Anytime you can market a guy making the league minimum as Jeter Reincarnate, ya do it.

With Domínguez et al, it’s as simple as giving fans a reason to even tune in at this point. The Yankees have not only sucked, they’ve been boring, and with the playoffs out of reach, it’s time to give people something to look forward to for next year. It’s no coincidence that as soon as these guys got called up, they got a horrible catch-all nickname. It’s also no coincidence that Hal was both heavily involved in the shortstop job decision, and reportedly overruled the front office in calling up the Y****** Y****. Maybe not the most sound process, but hey, the fans are happy, right?

Ah well. Maybe the most crushing of all the blows this year was the news yesterday that Domínguez tore his UCL and will likely be out until sometime next summer. But it puts the Yankees in an interesting spot— how do you sell the fans on 2024 now? The Martian was the de facto face of the team’s budding youth movement, arguably surpassing Volpe in his brief stint in the bigs. Will the promise of Peraza, Pereira and Wells be enough to keep Yankeeland willing to shell out $24.99/mo for a buggy YES app, and like, $18 on a Stadium beer? Or will Hal be forced to crack open the piggybank, possibly for a certain left-handed slugger who can play center field and first base, who’s in his prime and even alluded to a personal affinity for the pinstripes? How the young guys fare in the final 19 games of the season might help determine all that. But Hal should remember one thing: he is dealing with some sick, sick, people.